Europäische Sozialforum 2008, Malmö

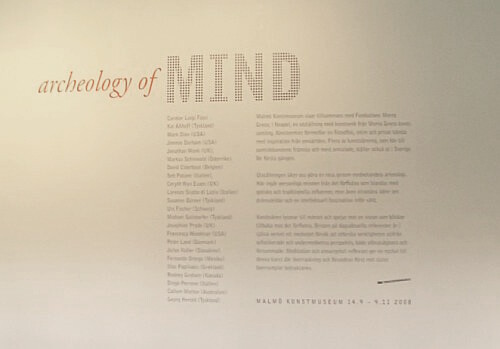

Kunst-politischer Kritik der Ausstellung "Morra Grecos Fondation Art Collection: Archeology of Mind" im Malmö Konstmuseum

Ankündigung im ESF Programm

"What does it mean when the publicly-financed Malmö Konstmuseum showcases a millionaire's fine taste?

What of the "art quality" of the works involved? Are there any non-commodity alternatives — absent from this exhibition – that really do build on the legacy of historic avant-gardes? This unconventional exhibition tour hopes to offer participants a chance to consider these issues."

Zusammenfassung (Englisch)

Nine people from three countries took part in the workshop, which lasted close to three hours. I visited the exhibition the previous day, focusing on the works, developing my critique of the hanging and selection. When I then had a look at curator Luigi Fassi's handout text (click for PDF), I saw that it was designed to anticipate and deflect many points of my critique. I then spent the evening before the workshop doing a rhetorical reading of the text, in which Fassi marshals Nietzsche's essay "On the Use and Abuse of History for Life" to his defense.

I explained my method at the start of the workshop, stressing this fact to the group: a large arsenal of means is deployed in the art system towards unshakeably legitimating what are already dominant groups, actors, and tendencies. These are challenging—but not impossible—to contest, and the workshop aimed to engage participants in this movement.

A "curated" exhibition "from" the Morra Grecos foundations art collection hinges on this ambiguity: does its monochromatic, retro-surrealist emphasis show that the collection is so broad and multifaceted that it is possible to assemble very disparate (but sizable) subgroups within it? Or is the "curatorial theme" actually an alibi to explain the collector's taste?

The Malmö Konstmuseum participates, very unscientifically (for a museum, it must be said!) in this ambiguity because it:

1/ Forfeits the entire communication to the invited curator/foundation

2/ Doesn't provide any of the (well and truly art-historical) background on who this patron, Maurizio Morra Grecos, is; how he made his money; how his foundation operates...

Instead we have layer over layer of discourse and posture that

1/naturalizes (see underlined sections of PDF, 1st page) and

2/depersonalizes ("the temporal gap becomes the detonator of meaning")

what were actually conscious, criticizable, and reversible decisions.

The workshop participants split into subgroups as we walked through the exhibition. Gathering together, we exchanged impressions, made connections between the works and noted their organization and hanging according to (unexplicited) genre clichés: the memento mori cycle, the cabinet de curiosités cycle, the portrait cycle, the landscape cycle. It was easy to be reminded of Nathalie Heinich's thesis that a convention of contemporary art is to play with references while maintaining ironic distance (Le triple jeu de l'art contemporain, 1999).

On the experiential level of the reception of the works, all remained thoroughly muséal: no touching, no interaction, no internet works or media work other than video. Only one work documented an intervention in public space. The exhibition and text cultivated a throwback image of the lone male artist (20 of the 22 featured artists were men!) working in his studio, a notion the Russian avant-garde writers and artists already dismissively called easelism (stankovizm) in the 1920s.

Most works strived at a retro-surrealist "look", or made oblique references to avant-gardes of the twenties, fifties, or sixties (Wyn Evans collages quote Fontana+Baldessari; a Dion object harkens to Broodthaers, a Rodney Graham video quotes Cage prepared piano pieces). The works were mostly austere in their palettes, and a few vaguely sinister in an adolescent way. Several recently produced works were assemblages or collages that included artifacts several decades old. More politicized avant-gardes were not quoted (and emphatically not present in the exhibition). The "retro" strategy conveniently provided cover for the most fetishistic hanging methods (drawings in canson passe-vues under glass and massive frames: Markus Schinwald).

Curator Fassi encapsulated this dimension with his fatuously programmatic statement: "Such conscious outdatedness appears to bring to the surface the most prolific ideas that, within the history of European thinking, have helped bring about a revolutionary and innovative approach to historicising (sic.) tradition."

He then harkened to the aforementioned Nietzsche essay, somewhat simplifying the philosopher's argument when he referred to his concepts of antiquarian and monumental history while revealingly leaving Nietzsche's critical history out of the account. Worse, he lopsidedly presented Nietzsche as championing monumental history: "Past events that are gathered together by monumental history must exist only for the benefit of dynamic expansion of the current time (...) This Nietzschean image of the past as a place of mythologically positive power (...) restores the meaning of a creative use of the past and of its inspiration." Upon this mistaken reading, Fassi concluded that Archeology of Mind takes up "this perspective."

Without going into detail into the antidemocratic dimension of the thought of Nietzsche and several of his post-modern followers (on this point, see Jan Rehmann, Postmoderner Linksnietzscheanismus: eine Dekonstruktion, 2004), or the tortured political lineage the philosopher has spawned, it is striking that even Nietzsche himself does not lend himself so easily to the politically neoconservative instrumentalization Fassi attempted to pull on him.

Nietzsche warns in the same essay: "There are times when we cannot distinguish between monumental history and mythic fiction. Thus, if the monumental considerations of the past rule over other forms of analyzing it, over the antiquarian and critical methods, then the past itself suffers harm."

It is tempting to hijack Nietzsche's antidemocratic characterization of the "dancing swarm" of "feebly artistic natures," in order to re-inscribe his warning against the "customs of popular agreement" into a critique of those "customs" arising from the class hegemony. His attack fits Fassi and Morra Grecos like a glove. Nietzsche depicts such "connoisseurs" as motivated by the view that "the monumental must definitely not be produced again." He concludes, damningly: "so they are knowledgeable about culture because they want to get rid of culture."

This point was discussed in the exhibition with the workshop participants. A short discussion ensued about the competing avant-gardes and approaches the show and text negated (despite its ostensible historical concerns).

I then asked: what kind of "culture" is one in the presence of when a curator's museum-pedagogical material takes so many hackneyed and derealizing (Bourdieu) turns?

To me, Fassi's essay, amplified by the posture of many of the auratically disposed works, seemed to say: "Back off from trying to understand it all. History is a special substance which is difficult ("recondite") and locked away in Foundations."

Furthermore, the show seemed designed to leave viewers relieved and thankful the works were themselves easy to look at (compared with the text) and quite conventional, then leaving the museum feeling human and not stupid like the football fans, but obviously less gifted than the inspired curator, artists, and collector—and grateful to the city municipality for this edifying bit of tasteful, secular grandeur, rebelliousness, and mystery.

The aformentioned Nietzsche quote deserves one more look. It actually seems quite adapted to this reading of recent history (one that contextualizes the exhibition and that the Malmö Konstmuseum will perhaps heed to next time a Social Forum comes to town): capitalist collectors are knowledgeable about culture—their culture of commodities, artifacts, the trivia and lives of the artists that are servile to them—because they want to get rid of the culture of subaltern resistance, revolutionary ideas, paradigmatic breaks that the historical avant-gardes embody. For them, the monumental is not to rise once more; and the bourgeois revolution of 1789 is not to be superseded by any lasting change, be it revolutionary or not, which may topple the current structures of domination.